Server: Apache/2.0.54 (Debian GNU/Linux) PHP/4.3.10-18

Content-Length: 1742

Connection: Keep-Alive

200 OK

A.I.R extension #00/interview with Bulent Tanju

We’re sitting here in the Marmara Hotel with a bird’s eye view on Taksim Square. In your catalogue essay for this year’s biennial you refer to Taksim Square as a stage of representation. A representation of what exactly?

Of everything really, the expression refers not to a specific topic of representation but to the general logic of representation, or more precisely my position with respect to the idea of a representational logic. So Taksim Square is a stage of representation, but in a way we can consider any part of the city as a stage of representation.

Any specific players performing on this stage?

There are numerous urban and architectural means to create the illusion of representation. As a matter of fact every object, every practice can be a tool to create this illusion. Think about the headscarf for instance and the laicist argument against it, that it’s representing a religious belief.

The concept of the logic of representation refers more to the idea that some truths seem to be given, they just stay there and people use specific tools as we said to represent them, almost like an icon actually. It’s a kind of “religious” way of thinking. If you see somebody with a headscarf you may think she is a religious fundamentalist, if you see somebody with a suit and tie. you may think he is secular, and so-called westernized and modern. For me this is not only a very simplified view. For me it is wrong. We don’t represent anything in that way. Compare it to writing. Many people think about things and then write it down. Whereas actually we think through writing, not before we write. Thinking through writing is a kind of creation. It does not belong to the logic of representation. It is a practice through which we create something new.

You describe language as a dynamic system that allows you to establish a moment in your thinking to communicate to others. It reminds me a lot of Agamben’s ideas on potentiality.

You can call it an event; something new appears.

I have the impression that this is the way you’ve described Taksim Square.

Yet in Turkey in a very heavy way people believe there should be some kind of truth that can be represented. There are lots of assumptions about this truth, objective, religious, but each of them represents the essentials that will give meaning and order to everything. To think in this way, you need to belief in representation, you have to find an objective way to represent these essential truths.

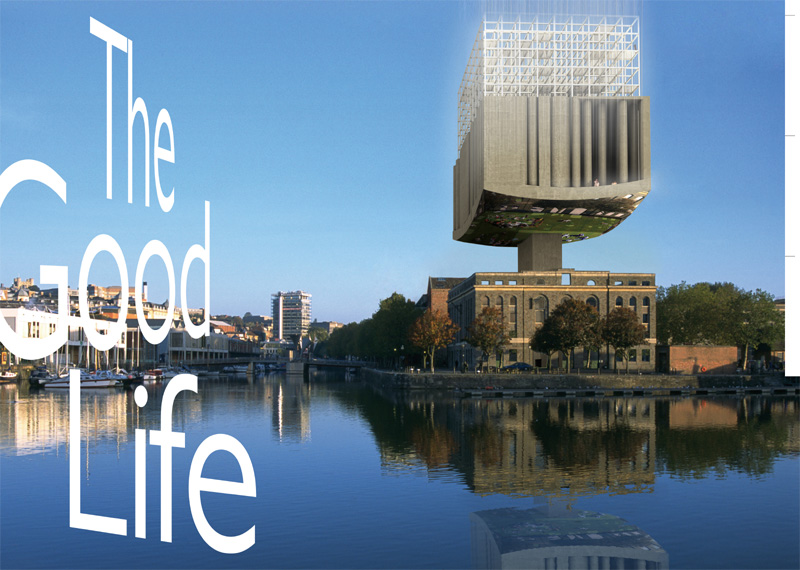

Does the Ataturk Kultur Mercesi (AKM building on Taksim) somehow fit into this picture? What is its position in the current debate?

It fits in this part of the story, because for a number of people what we call “culture” or “art” can represent the truth. Art is very important. If you look at the speeches of Atatuk you can feel that. People who are involved in the art practice are enlightened. They should create the representation of this single truth.

The attitude towards culture linked to state-organized cultural policies, very often has a protective, pedagogical undertone. In your essay you refer to the comprehension of culture as a greenhouse plant. Is the AKM not the physical incarnation of this view on culture?

I agree …

Do you see any conflict in terms of the biennials presence in the building? Do you think by selecting AKM as one of the main venues for this edition of the Biennial, Hanru made a legitimate choice?

Personally I think Hanru has kind of a naive conception of modernization actually. I told him I was going to write against the idea of modernization because I don’t think something like that exists. Because modernization suggests a kind of linear process, you get more and more modernized and finally become modern.

A form of teleological thinking…

Exactly, for me modernity means, actually to lose this kind of teleological point of view or target towards which we are supposed to move. It is a simple loss. It is the loss of the illusion of representation. We don’t belief any more in the representation. As I understand it, Hanru sees both IMC (another Biennial venue) and AKM as part of the modernization of Turkey. I think he considers these buildings, these structures in a very positive way. He probably considers them as representations of the modernization of Turkey, and that is very problematic for me

Because to you they are the opposite, they are actually confining this society to a certain stage, from which it is hard to escape?

I write on these structures and most of the narratives that were produced in this modern era as anti-modern. They were produced in order to control the multitude. They failed, but that was their intention: They are against modernity, they are against multitude.

So actually they are what they pretend to be fighting.

In Turkey for an outsider the struggle between secular and religious worldviews is obvious to observe. But somehow the conflict of interest becomes too obvious when you reduce contemporary social realities to just these two.

What is performed in the AKM is much closer to me than let’s say the religious views… But you are right to say it is not that simple. I usually differentiate between laicist and secular points of view. I don’t think there is a real secular layer in Turkish society. Actually there is, but they are a very small minority. The people that call themselves laicist, and the religious fundamentalists, in a way they are very close to each other, because they truly believe they know what should be done.

It makes me think of a Janus head; both sides of the coin constantly twisting around, without ever being able to observe each other, yet having the same goal, namely to be on top of things.

And if you look closely to the 20th century history of Turkey, then we have to reconsider. Actually some religious people and mainstream liberal, right wing politicians – the Kemalist republican elite calls itself the left, which is completely absurd – they tend to show much more openness to the outside world, are more open to differences. The funny thing is that throughout the republican period, the minorities – Christians, Jews, Armenians – they always voted for these liberal parties.

You can refer to them as liberal parties?

In economic terms they were liberal, from a general political point of view they were rather conservative. But still even then, they were more liberal than CHP, the founding party of Turkey.

In your essay you mention a third player next to secular and religious tendencies, one that has shown actual power to disrupt things.

We see four forces operating – it is a too simplifying way to describe it, but still. The first category is the founding or republican elite. They still exist. They have very complex relations with other groups, but they are still around, especially among the military, the state bureaucracy, the court systems, the universities…

Let’s say a capitalist who is independent from the state, a truly free entrepreneur that is a relatively new phenomenon, appearing after the 1980ies. Sometimes we see that these people are also very religious. I think this is very important because a religious capitalist is something new in Turkey. And I give these kind of actors great importance because it is a very difficult task being a religious man or woman and at the same time a hard line capitalist.

For us it is not uncommon to connect worldly affairs with some divine notion or religious conviction. I think Protestants for instance accumulate their riches as a way of serving God.

I know, and people also compare these kind of histories. I’m not sure whether we can compare them or not. It simply means that someone tries to connect religion and money, or religion and daily life. That’s important because it constitutes a little transformation in the rules of religion, so in a sense religion becomes a bit ‘secular’ actually, a bit more open.

The AKP is definitely conservative but they are truly a worldly power. And that’s how they see themselves. This is very important, because in that sense things can be discussed with them. They are worldly so we can discuss with them issues like for instance the headscarf.

There is this organization in Turkey that rules the university system. The head of this institution is a professor, he is a lawyer and he doesn’t want to discuss anything that has to do with the headscarf.

Yes, I just read it in the newspaper; he actually says that trying to lift the ban on wearing a headscarf in universities is illegal. But then I thought, the law is a construction, right, something a number of people agree upon in a specific context, namely parliament.

Yes, exactly.

The traditional parties as far as I can tell, have less open views on society. As a secular person myself I would have a very hard time deciding who to vote for. The republican program wasn’t that appealing, for me it had no view on contemporary problems.

It’s much worse. They have a view. They are nationalist, and – I don’ know how they managed to do that – they are part of the European Union of Socialist Parties. Just connect those two concepts, and you know that they are a dangerous force in our society.

During the late 60ties and 70ties this party had a kind of a social democratic profile. At that time the real leftist movements were very powerful in Turkey. We also had very influential labor unions in this period. Somehow the republican party was able to link itself to this debate in our society, and for a moment became a credible alternative. I remember for a lot of people of my parents’ generation this created a kind of hope, the hope of real democratic reforms. But it didn’t happen. We had a military coup in 1980, which kept the generals visibly in power for 3 years. In 1982 they introduced the new constitution written by generals. Actually that one is still functioning to the present day. AKP is the first party that is questioning it and will propose to rewrite it. None of the other parties ever tried to change it.

This year’s biennial is the 10th edition, so counting back, the first edition took place in 1987. It must have been a different social and political context in which it was set up. How was the reception of these first editions of what has now become an internationally acclaimed event?

In view of what we have been discussing, it’s rather funny to say but contrary to all republican discourse – because officially they were for the arts, for all the western ideas on art, westernized forms of life, etc – actually they were never that open to art. Because if you are really open to creation, open to a contemporary practice, it creates numerous problems. It creates crises. What makes art important for me is that it puts us into a crisis actually. When we seem too sure about anything, it disrupts it. It is a kind of a critical process for me. So the republican discourse was actually looking for a limited form, maybe just the facade of the arts. They were very calculated performances on the stage of representation. Actually the current policy of AKP is much more open. Not that they engage into this critical process, but they have simply realized that art is something very important everywhere. It is an important player that can create financial resources.

They see the symbolic value of the Istanbul Biennial, also in an international context. They find it a useful tool to disseminate their own narrative. That’s why Erdogan pushed things in order to be able to open Istanbul Modern before addressing the European issue, something which he repeated only a couple of months ago when he opened Santralistanbul, the major renovation of an old power plant into a pristine site with a contemporary art museum, a public library and the Bilgi university (a private university)

One can say that relatively spoken, the recent editions of the biennial have been better funded, both privately, by the municipality and the state, because they realize the event creates an added value for the city and the country. It creates a dynamic. Plus the biennial is getting bigger, and more international.

Not Only Possible But Also Necessary: Optimism In The Age Of Global War is the title Hanru gave to this edition. The biennial takes as its theme different modernities as they take shape around the globe, and in that respect I think it has political relevance. But in doing so it seems to contests some of the economic realities of which it is actually a part.

I’m usually very critical to all things related to Turkey, and yet I still live here. In that sense we continuously share the same bed, all of us. For me that’s life actually. So, yes it is a contradiction, but on the other hand we work through these contradictions, that’s all. I hope we don’t dream about any situation without contradictions. I think the main thing is what we can do through these contradictions. I don’t expect any perfect biennial, politically correct, well funded… It would be almost contradictory to life itself and probably a bit boring.

Let me rephrase the question and relate the biennial to its presence in AKM. Do you think there is a possibility this event may change AKM’s former identity?

I don’t know. I think it’s possible but it depends on many circumstances, the people of the foundation, the visitors, the artists. I truly believe that the arts are the most important factor in the destruction of the logic of representation. For me the only thing art history teaches me is the destruction of our believe in representation. Writers, painters, even they believed they were going to create the fundamental tool of representation. But they all failed, and it’s a very important failure actually. Arts still are the most open practice in this sense.

The other day we spoke to a young Turkish journalist; we visited AKM together. For him the building has to come down. It symbolizes too much a form of repression that did its utmost best to present itself as an open society. He told me that for an outsider it would be difficult to understand.

There is a lot of discussion on the future of AKM, whether it should be taken down and replaced by something else or not. I found my point of view on this question through writing the essay for the biennial. First of all, through my personal history I can relate to this building. I don’t like the governing idea behind it, but I spent a lot of time inside. We can say it made a lot of things possible in its history: a lot of extraordinary productions were created on its stage. It is true that it can be organized as a disciplinary tool, as an educating or repressing tool, but it has also worked in other ways. Deleuze talks about the control society, repression, etc… and in the end he states, “… anyway society leaks”. You cannot control everything, it leaks all the time. So the AKM has leaked since its existence. The initial intention is not that important, what is important is what we are doing with that building, with this part of the city, etc. In that sense I’m against the destruction of AKM. Not from the standard cultural heritage point of view, not the standard preservation policies. I don’t want to make any distinction between buildings and objects, saying that this belongs to our culture and this not. It does not mean anything to me. There is some stuff that has been built before me, and the only important thing is how I relate to it, what I do with it, how I can extent these objects and buildings. It’ s not even that they are the beginning. Again, I don’t like quotations, this is my last one, Deleuze says we are always in the middle of things, we are not at the beginning and not at the end. We are always in a process. Something that has been done, we can transform, use it in another way. To me the idea of AKM being a repressive building, we should tear it down and create another one that is not repressive, it still indicates a kind of ideal point, you know. We are going to find a building that is not repressive. But maybe it is not repressive at the point when it is constructed, but we do not know after 20, 30, 40 years…The building itself cannot be repressive actually only the way in which it is used can be. As I said a tie does not necessarily mean a modern, liberal person does it?

Bulent Tanju works as a writer, critic, curator and lecturer and is currently associate professor at the Department of Architecture of Yildiz Technical University, Istanbul.