News

Server: Apache/2.0.54 (Debian GNU/Linux) PHP/4.3.10-18

Content-Length: 1742

Connection: Keep-Alive

200 OK

A.I.R extension#10 (pavilion)

KATLEEN VERMEIR & RONNY HEIREMANS

Site-specific video installation for the 10th 10th STANBUL BIENNIAL

Not Only Possible, But Also Necessary:

Optimism in the Age of Global War - Istanbul (TR)

8 September – 4 November 2007

Press Conference 6 September / /

Professional Preview 7 September

curated by Hou Hanru

PRESS RELEASE

A.I.R is an ongoing project, encompassing various collaborations in different formats. Short for artist-in-residence, A.I.R refers to the appropriation of empty industrial spaces by artists in sixties New York. The project examines architecture as a significant ideological gesture. It allows Vermeir & Heiremans to deconstruct their own renovated postindustrial space as a system of representation, a comment on the modern habit of relating to architecture not from physical experience, but rather from magazines, television, exhibitions… Since 2006 they have been developing A.I.R as a series of mediated extensions of their habitat.

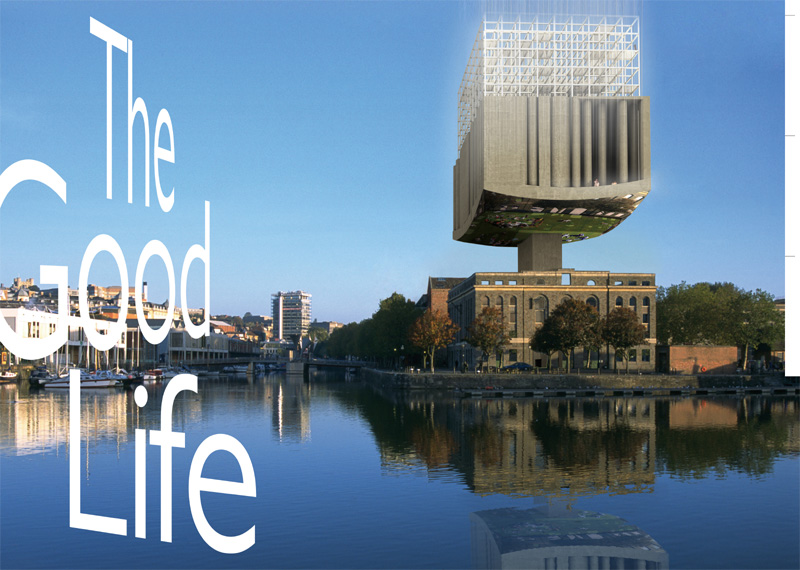

A.I.R extension#10 (pavilion) is a video installation, proposed for the AKM-building on Taksim Square, which functions as one of the temporary exhibition venues for the biennial. The project results from a residency at Platform Garanti in 2006.

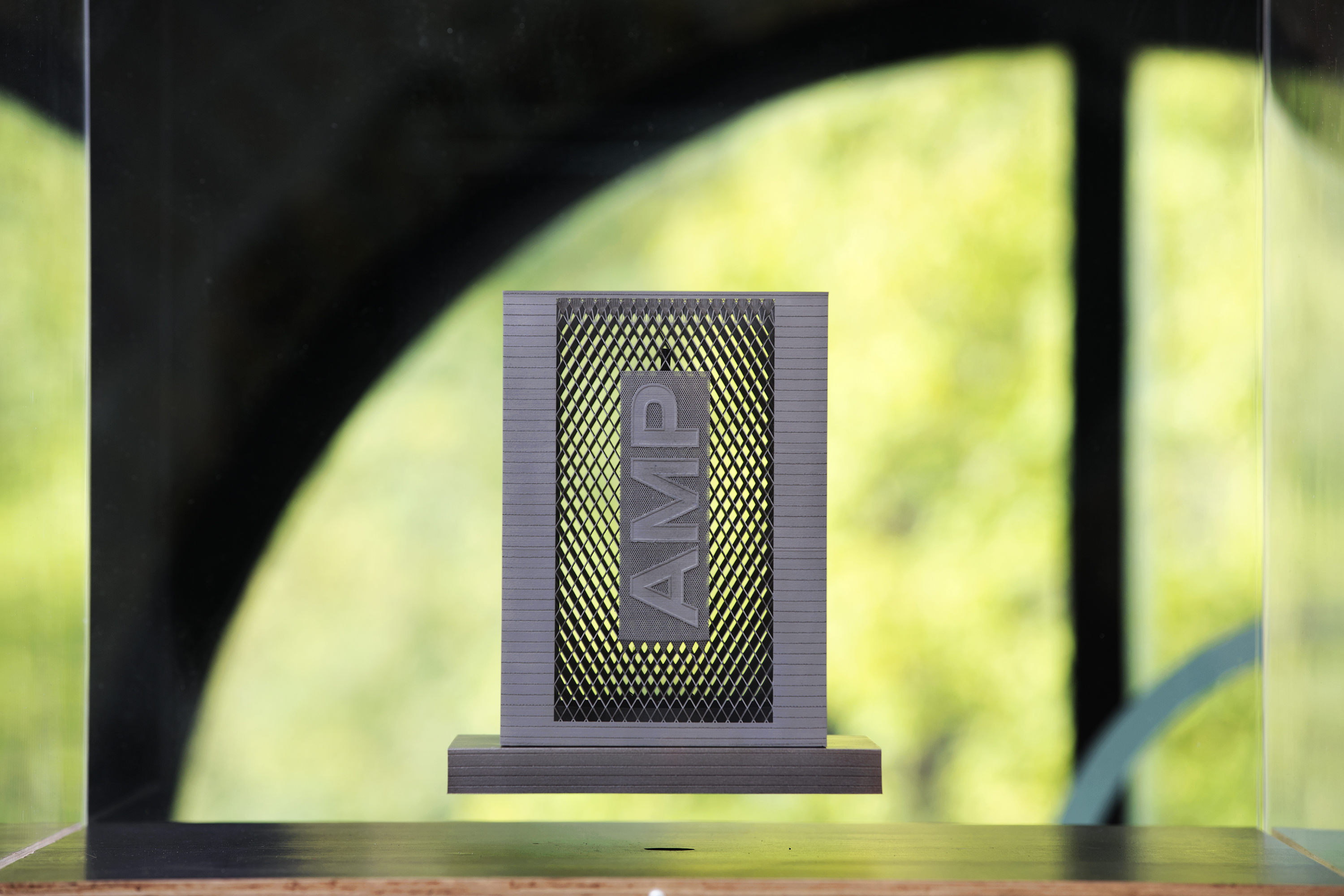

The installation proposes a semi-transparent ‘exhibition’ pavilion, functioning both as an annex (of their home) and as a framing device. The projection inside juxtaposes visuals of the Brussels loft space and imagery of Atatürk’s modernist marine pavilion in Istanbul. This summer residence, built by Seyfi Arkan in 1935, was a symbol of Turkey’s progressive modernity. The two spaces become mirroring clusters of meaning, embodied in architectural constructs in which the open floor-plan, the so-called lack of hierarchy and the use of transparency are essential. The video represents both edifices as showcases and devices to see the world. Inspired by Le Corbusier’s ‘promenade architectural’, overlapping frames are given temporality through movement. All images in the video are constructed. In this way Heiremans & Vermeir create a hybrid form, expressing a critical approach to modern architecture and to the alienating aspects of the video medium.

read text:

We came about this pavilion during a four month residency in Istanbul in 2006 at Platform Garanti. Its remoteness from the city centre makes it unknown to foreigners and unvisited by people living in Istanbul. Its extraordinary location and context prompted us to linking its ideological undercurrents with our research on the ideological appropriation of architecture in general and more specific in respect to our own domestic situation.

The Florya Atatürk Marine Pavilion, a horizontal composition constructed in the sea and connected to the Florya beach by a walkway, was commissioned by the founder of the modern Turkish State, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. It was built in 1935 by one of Turkeys most prominent adepts of Modernism, Seyfi Arkan. Taken into account the context in which it was designed and built, the Florya pavilion was to become emblematic of the progressive transformation of a society still rooted in the old Ottoman Empire. Modernist houses in 1930ies Turkey were promoted as emblems of modernization and westernization. They were showcased to disseminate a new vision of living to the whole nation and to exhibit to the rest of the world how the Turkish republic had stripped off its ‘oriental’ habits.

It was only used for a short period towards the end of Atatürk’s rule. He died in 1938, leaving the pavilion to future generations. Since 1993 the Marine Pavilion has been opened to the public as a museum.

Focusing on one aspect of Arkan’s Modernist building – transparency – the pavilion reflects Atatürk’s pragmatic recuperation of the Western concept of democracy and his view on women in society. Physical transparency in a building does not always guarantee its contribution to social transparency. It is often only in the photographs, the mediated circulations that buildings are displayed as transparent, rather than in the actual experience of them. Literally creating a façade of a transparent and open society, the Florya pavilion was to establish the necessary imagery of a leader amidst his people, ruling them but at the same time being part of them. The Florya pavilion was the residence in which Atatürk would spend his vacation, while socializing with the masses. He could wave his hand at them from the terrace of his ship-like building, the ship being a basic inspiration for modern architectural form (Le Corbusier became a major inspiration for Turkish architects in the early 30ies and was idealized as a reformer and true revolutionary. It is interesting to see how Kemalism was making use of modernism as a radical departure from its own Ottoman history, whereas Le Corbusier used certain elements of the Ottoman past as an inspiration to create his radically different housing models in the West.)

At the same time Atatürk’s liberating but paternalistic approach to women’s place in society finds an architectural expression in the pavilion. Transparency, an important component of the Modern Movement, was transported from Europe to Turkey, with a slight shift in meaning. The dissolution of boundaries between exterior and interior not only meant a closer relation with nature but the unveiled transparent house became also a trope for the unveiled Islamic woman. Glass was used to represent ‘progress’. According to feminists the reforms were a paternalistic program, casting women as objects of nationalist modernization. Images of women and modern architecture printed on the covers of magazines were proofs of the success of the new nation in dissociating from its Ottoman past, but this idealized image remained that of an enlightened wife and mother whose world was centered on the home.

ON ATATÃœRK KÃœLTÃœR MERKEZI (ATATÃœRK CULTURAL CENTRE) - TAKSIM SQUARE

The Ataturk Cultural Centre has become an interesting component of our project. In the same way as the Florya residence it was a prestige project for nation building in the 30ies. The proclaimed modernist transparency of the building appears to be one sided: you can see everything from within; from the outside it is an impenetrable black box fortified with a concrete and steel structure which gives the building its eloquence but at the same time renders it completely closed. The steel structure outside functions as a screen: a conservative way to control the gaze in a technically innovative way.

Also inside the building the materials used are cause for perceptual ambiguities: the use of big mirrors, glass and plexi in many varieties, creates openness and confusion. The physical aspects of the Centre determined in a significant way the form our hybrid ‘exhibition’ pavilion has taken.

HISTORY & BIENNIAL LOCATION

In the mid-1930s, to meet the need for a performance hall for western style cultural events, architect Auguste Perret was asked to design an opera house for the Taksim Square in Istanbul. The construction was interrupted several times and different architects worked on the project. Finally the opera house was transformed into a cultural centre by the architect, Hayati Tabanlioglu with the decision of the Ministry of Public Works and was opened in 1969 under the name “Istanbul Cultural Palace”. A big fire in 1970 led to the closure of the building to the public. After renovations it was reopened in 1978 and given the name Ataturk Cultural Centre. Seating 1307 people, its grand hall is used for opera, ballet, theatre and classical music performances while the second hall holding 502 people is mostly used for concerts. Large foyers on each floor combine the halls smoothly. Art galleries on the top floor cover an area of 1200m� in total. A leading example of the Republican Period Architecture and a symbol of the Taksim Square, the heart of Istanbul, the AKM Building serves as a major element of the city’s cultural memory. Obviously, this modernist edifice incarnates the ideological model of Turkey’s modernization driven by its republican revolutionary project. However, it’s facing the destiny to be gentrified by today’s global capitalism’s expansion. Using this building as an important venue for the biennial with an exhibition focusing on the question of utopia and its fate all around the world, questions of social progress, modernization and democracy, etc. in the current conditions of globalization will be raised and debated. In the meantime, it’ll help the public to rediscover the significance of the building itself.

Sources:

Sibel Bozdogan; ’Modernism and nation-building: Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic’, 2001

Beatriz Colomina; ‘Privacy and Publicity. Modern Architecture as Mass Media’, 1996